Probably the most common credit card business model is for customers to be charged a small annual fee in return for which they are able to make purchases using their card and to only pay for those purchases after some interest-free period – often up to 55 days. At the end of this period, the customer can choose to pay the full amount outstanding (transactors) in which case no interest accrues or to pay down only a portion of the amount outstanding (revolvers) in which case interest charges do accrue. Rather than charging its customer a usage fee, the card issuer also earns a secondary revenue stream by charging merchants a small commission on all purchases made in their stores by the issuer’s customers.

So, although credit cards are similar to other unsecured lending products in many ways, there are enough important differences that are not catered for in the generic profit model for banks (described here and drawn here) to warrant an article specifically focusing on the credit card profit model. Note: In this article I will only look at the profit model from an issuer’s point of view, not from an acquirer’s.

* * *

We started the banking profit model by saying that profit was equal to total revenue less bad debts, less capital holding costs and less fixed costs. This remains largely true. What changes is the way in which we arrive at the total revenue, the way in which we calculate the cost of interest and the addition of a two new costs – loyalty programmes and fraud. Although in reality there may also be some small changes to the calculation of bad debts and to fixed costs, for the sake of simplicity, I am going to assume that these are calculated in the same way as in the previous models.

Revenue

Unlike a traditional lender, a card issuer has the potential to earn revenue from two sources: interest from customers and commission from merchants. The profit model must therefore be adjusted to cater for each of these revenue streams as well as annual fees.

Total Revenue = Fees + Interest Revenue + Commission Revenue

= Fees + (Revolving Balances x Interest Margin x Repayment Rate) + (Total Spend x Commission)

= (AF x CH) + (T x ATV) x ((RR x PR x i) + CR)

Where AF = Annual Fee CH = Number of Card Holders

T = Number of Transactions PR = Repayment Rate

ATV = Average Transaction Value i = Interest Rate

RR = Revolve Rate CR = Commission Rate

Customers usually fall into one of two groups and so revenue strategies tend to conform to these same splits. Revolvers are usually the more profitable of the two groups as they can generate revenue in both streams. However, as balances increase and approach the limit the capacity to continue spending decreases. Transactors, on the other hand, seldom carry a balance on which an issuer can earn interest but they have more freedom to spend.

Strategies aimed at each group should be carefully considered. Balance transfers – or campaigns which encourage large, once-off purchases – create revolving balances and sometimes a large, once-off commission while generating little on-going commission income. Strategies that encourage frequent usage don’t usually lead to increased revolving balances but do have a more consistent – and often growing – long-term impact on commission revenue..

Variable Costs

There is also a significant difference between how card issuers and other lenders accrue variable costs.

Firstly, unlike other loans, most credit cards have an interest free period during which the card issuer must cover the costs of the carrying the debt.

The high interest margin charged by card issuers aims to compensate them for this cost but it is important to model it separately as not all customers end up revolving and hence, not all customers pay that interest at a later stage. In these cases, it is important for an issuer to understand whether the commission earnings alone are sufficient to compensate for these interest costs.

Secondly, most card issuers accrue costs for a customer loyalty programme. It is common for card issuers to provide their customers with rewards for each Euro of spend they put on their cards. The rate at which these rewards accrue varies by card issuer but is commonly related in some way to the commission that the issuer earns. It is therefore possible to account for this by simply using a net commission rate. However, since loyalty programmes are an important tool in many markets I prefer to keep it out as a specific profit lever.

Finally, credit card issuers also run the risk of incurring transactional fraud – lost, stolen or counterfeited cards. There are many cases in which the card issuer will need to carry the cost of fraudulent spend that has occurred on their cards. This is not a cost common to other lenders, at least not after the application stage.

Variable Costs = (T x ATV) x ((CoC x IFP) + L + FR)

Where T = Number of Transactions IFP = Interest Free Period Adjustment

ATV = Average Transaction Value CoC = Cost of Capital

FR = Fraud Rate

Shorter interest free periods and cheaper loyalty programmes will result in lower costs but will also likely result in lower response rates to marketing efforts, lower card usage and higher attrition among existing customers.

The Credit Card Profit Model

Profit is simply what is left of revenue once all costs have been paid; in this case after variable costs, bad debt costs, capital holding costs and fixed costs have been paid.

I have decided to model revenue and variable costs as functions of total spend while modelling bad debt and capital costs as a function of total balances and total limits.

The difference between the two arises from the interaction of the interest free period and the revolve rate over time. When a customer first uses their card their spend increases and so does the commission earned and loyalty fees and interest costs accrued by the card issuer. Once the interest free period ends and the payment falls due, some customers (transactors) will pay their full balance outstanding and thus have a zero balance while others will pay the minimum due (revolve) and thus create a balance equal to 100% less the minimum repayment percentage of that spend.

Over time, total spend increase in both customer groups but balances only increase among the group of customers that are revolving. It is these longer-term balances on which capital costs accrue and which are ultimately at risk of being written-off. In reality, the interaction between spend and risk is not this ‘clean’ but this captures the essence of the situation.

Profit = Revenue – Variable Costs – Bad Debt – Capital Holding Costs – Fixed Costs

= (AF x CH) + (T x ATV) x ((RR x PR x i) + CR) – (T x ATV) x (L + (CoC x IFP)) – (TL x U x BR) – (TL x U x CoC + TL x (1 – U) x BHR x CoC) – FC

= (T x ATV) x (CR – L – (CoC x IFP) -FR) – (TL x U x BR) – ((TL x U x CoC) + (TL x (1 – U) x BHR x CoC)) – FC

Where AF = Annual Fee CH = Number of Card Holders

T = Number of Transactions i = Interest Rate

ATV = Average Transaction Value TL = Total Limits

RR = Revolve Rate U = Av. Utilisation

PR = Repayment Rate BR = Bad Rate

CR = Commission Rate CoC = Cost of Capital

L = Loyalty Programme Costs BHR = Basel Holding Rate

IFP = Interest Free Period Adjustment FC = Fixed Costs

FR = Fraud Rate

Visualising the Credit Card Profit Model

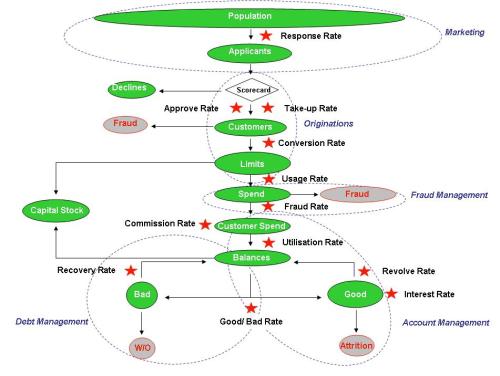

Like with the banking profit model, it is also possible to create a visual profit model. This model communicates the links between key ratios and teams in a user-friendly manner but does so at the cost of lost accuracy.

The key marketing and originations ratios remain unchanged but the model starts to diverge from the banking one when spend and balances are considered in the account management and fraud management stages.

The first new ratio is the ‘usage rate’ which is similar to a ‘utilisation rate’ except that it looks at monthly spend rather than at carried balances. This is done to capture information for transactors who may have a zero balance – and thus a zero balance – at each month end but who may nonetheless have been restricted by their limit at some stage during the month.

The next new ratio is the ‘fraud rate’. The structure and work of a fraud function is often similar in design to that of a debt management team with analytical, strategic and operational roles. I have simplified it here to a simple ratio of fraud: good spend as this is the most important from a business point-of-view, however if you are interested in more detail about the fraud function you can read this article or search in this category for others.

The third new ratio is the ‘commission rate’. The commission rate earned by an issuer will vary by each merchant type and, even within merchant types, in many cases on a case-by-case basis depending on the relative power of each merchant. Certain card brands will also attract different commission rates; usually coinciding with their various strategies. So American Express and Diners Club who aim to attract wealthier transactors will charge higher commission rates to compensate for their lower revolve rates while Visa and MasterCard will charge lower rates but appeal to a broader target market more likely to revolve.

The final new ratio is the revolve rate which I have mentioned above. This refers to the percentage of customers who pay the minimum balance – or less than their full balance – every month. On these customers an issuer can earn both commission and interest but must also carry higher risk. The ideal revolve rate will vary by market and depending on the issuers business objectives but should be higher when the issuer is aiming to build balances and lower when the issuer is looking to reduce risk.