Too many prisons make bad people worse. There is a better way - The Economist - May 27th 2017

The world can learn from how Norway treats its offenders

“DO YOU want a coffee?” It is a chilly morning on the ferry to Bastoy, an island prison in Norway. Two burly ferrymen greet a visiting journalist with a hot drink. Asked if they work for a local ferry company, they reply: “No, we are prisoners.” One is serving 14 years for attempted murder. The other, nine years for “drugs and violence”. The ferry is moored and there is no one around. Either man could easily make a run for it. But neither does. Hardly anyone tries to escape from Bastoy.

It has been called the “world’s nicest prison”, but this misses the point. The rooms are pleasant enough. The inmates can wander where they like on the island, go cross-country skiing in the winter and fish in the summer. So long as they keep it tidy they can enjoy the beach (see picture). Yet what is most unusual about Bastoy is not that it treats prisoners like human beings, but that it treats them like adults.

Prisons in other parts of the world try to stop inmates from laying hands on any piece of metal that could be shaped into a weapon. Bastoy prisoners walk around with hammers, axes and chainsaws. They chop down trees for furniture, grow vegetables and raise livestock. They used to slaughter cows but Norwegian health and safety laws make this uneconomical unless done on an industrial scale.

In short, the prisoners are expected to look after themselves. If they do not tend the forest, it will cover the island, notes Tom Eberhardt, the governor. If they do not tend the fields, the crops will die.

Inmates do not start their sentences at Bastoy. They must do time in a conventional lockup and apply to be transferred, having convinced the authorities that they wish to reform. In a normal prison, inmates are spoon-fed, notes Mr Eberhardt. “They take only three or four decisions a day, such as when to go to the toilet.” At Bastoy they make nearly as many decisions as they would if they were free. By teaching the inmates responsibility, Bastoy aims to “create good neighbours”.

Norway has the lowest reoffending rate in Scandinavia: two years after release, only 20% of prisoners have been reconvicted. By contrast, a study of 29 American states found a recidivism rate nearly twice as high. This is despite the fact that Norway reserves prison for hard cases, who would normally be more likely to reoffend. Its incarceration rate, at 74 per 100,000 people, is about a tenth of America’s.

Visiting Americans find the atmosphere at Bastoy shocking. Why is security so lax? Where are the lethal electric fences and the guards with shotguns? At a prison in Indian Springs, Nevada, your correspondent was advised not to wear blue because that was the colour of the prison uniform. It was unlikely that there would be trouble, the press officer explained, but if there was you would not want an armed guard to mistake you for a rioting inmate.

Nelson Mandela once observed that: “No one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails.” This article makes a different argument: that although they have improved in recent decades, the world’s prisons are nowhere near as effective as they should be at curbing crime or reducing harm to society. Far too many fit the description of Douglas Hurd, a former British home secretary, who said that: “Prison is an expensive way of making bad people worse.”

What ails the jails

There are at least 10.3m people behind bars worldwide, according to Roy Walmsley of the Institute for Criminal Policy Research, a think-tank. This is a snapshot—many more pass through each year and yet more are on parole or probation. The global total excludes countries such as North Korea and Eritrea, which have big gulags but publish no data. It also undercounts the number in China, which has not recently revealed how many of its people are locked up awaiting trial.

Since 2000 the number of prisoners in the world has risen by 20%, a little above population growth of 18%. The trend masks a frenzy of regional change. South America, South-East Asia and the Middle East have seen sharp increases in prisoner numbers (145%, 75% and 75%). In Europe numbers have fallen by 21%. Over the same period, crime has fallen worldwide.

Many jails are hellish; sometimes deliberately so. In Syrian prisons, dissidents are beaten, given electric shocks, crushed in a folding board called the “flying carpet” and hanged in their thousands after two-minute “trials”. More commonly, prisons are vile because they are overcrowded and ill-managed, so the nastier inmates (and guards) can do what they please.

At some Brazilian lockups, for example, heavily outnumbered guards patrol the perimeter and allow gang bosses to impose order within. Convicts are free to run their drug empires by mobile phone. In the first two weeks of 2017, as rival gangs fought for supremacy, at least 125 inmates were killed in riots in Brazil. At one prison in Manaus, severed heads and limbs were stacked on the floor.

Worldwide, overcrowding is the norm. Prisons cost money to build, after all, and there are few votes to be won by making life easier for criminals. In 58% of the 198 countries for which there are data, prisons are more than 100% full, says the latest annual Global Prison Trends report from Penal Reform International, a think-tank. Some 40% of countries were above 120% capacity; 26% were above 150%.

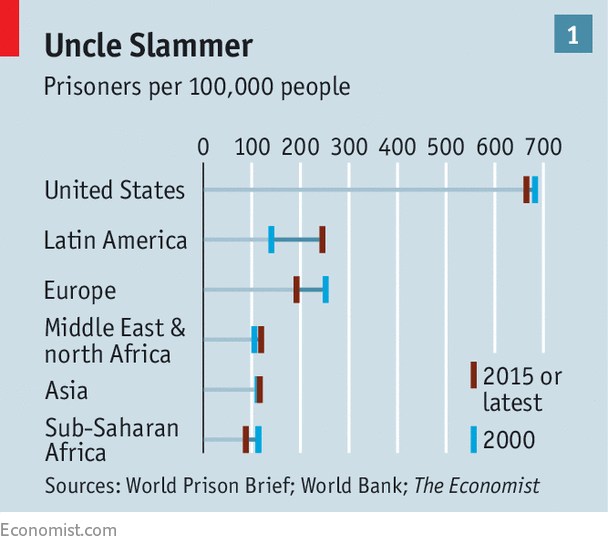

America locks up far more people than any other rich country (see chart 1). Yet the recent trend has been towards leniency. The proportion of American adults behind bars fell from a peak of 1 in 100 in 2008 to 1 in 115 in 2015. Several states have tried to find alternatives to incarceration for non-violent criminals, partly to save money and partly because they have concluded that locking up too many people for too long does little for public safety. “Kentucky prisons were full of people we’re mad at, not people we’re afraid of,” says John Tilley, the secretary of justice in Kentucky.

On the straight and narrow

Donald Trump’s attorney-general, Jeff Sessions, wants to make America more punitive again. This month he ordered federal prosecutors to seek maximum sentences for drug offenders. Although federal inmates are less than a tenth of the total in America, Mr Sessions shows that advocates of old-fashioned “tough-on-crime” policies are still powerful.

One reason for locking people up is to punish them. Victims of crime, especially, may be comforted by the knowledge that their tormentors are suffering. In a poll in crime-racked Brazil, 57% of people agreed that “a good criminal is a dead criminal.”

But for many people the aim of incarceration is to reduce the harm caused by criminals. Prisons can do this in three ways. First, they restrain: a thug behind bars cannot break into your house. Second, they deter: the prospect of being locked up makes potential wrongdoers think twice. Third, they reform: under state supervision, a criminal can be taught better habits.

On the first count, most prisons succeed, but at a cost. The mass incarceration of certain groups of men, such as black Americans, can tear apart families and communities. And many criminals are kept locked up long past the age at which they cease to pose much of a risk to the public. Violence is a young man’s vice; there are not many middle-aged muggers.

On the second count, deterrence, prisons are necessary unless we want to bring back flogging. But sentences need not be as long as they are in many countries, especially America. Criminals have short time horizons—a ten-year sentence only deters them slightly more than a one-year sentence, though it costs ten times as much. To deter would-be criminals, what matters most is not the severity of the penalty but the certainty and swiftness with which it is imposed. Criminals restrain themselves only if they think they will be caught and punished. Steven Levitt, an economist, estimates that in America $1 spent on police is at least 20% more effective in preventing crime than $1 spent on prisons.

Even when the police are effective, criminals are often undeterred. They are typically impulsive and opportunistic, picking fights because they are angry and grabbing loot because it is visible. Which is why rehabilitation is so important: nearly all inmates will eventually be released, and it is far better for everyone if they do not go back to their old ways.

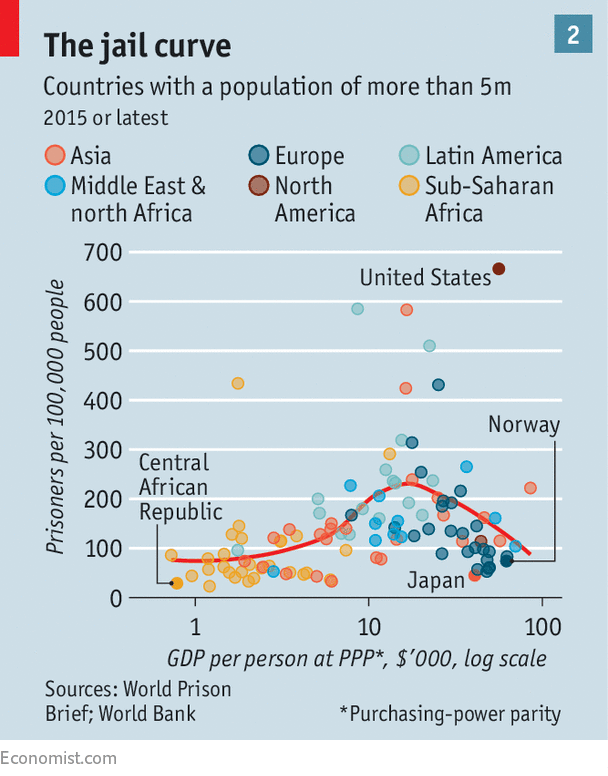

The countries that lock up the fewest people tend to be either liberal (Sweden, Finland) or too poor to build many prisons (see chart 2). In the Central African Republic, the incarceration rate is only 16 per 100,000. (By one estimate half the inmates are serving time for witchcraft.)

Reserving prison for the worst offenders has hefty benefits. First, it saves money. In America, for example, incarcerating a federal convict costs eight times as much as putting the same convict on probation. Second, it avoids mixing minor offenders with more hardened criminals, who will teach them bad habits. “The low-level guys don’t tend to rub off on the higher-level prisoners. It goes the other way,” says Ron Gordon of the Utah Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice, a state body.

Modern electronic tags are cheap and effective. In a recent study Rafael Di Tella of Harvard University and Ernesto Schargrodsky of Torcuato Di Tella University compared the effects of electronic tagging versus prison for alleged offenders in Buenos Aires. Earlier research had failed to deal with the fact that criminals who are tagged are less likely to reoffend than the more dangerous ones who are locked up. The authors found a way round this. Alleged criminals in Argentina are assigned randomly to judges for pre-trial hearings. Liberal judges are reluctant to hold them in the country’s awful jails, so they often order them to be tagged. So-called mano dura (tough hand) judges prefer to lock them up. The researchers observed what happened to similar offenders under different regimes. Only 13% of those who were tagged were later rearrested; for those sent to prison the figure was 22%.

Prison break

Some criminals are so dangerous that they need to be locked up. But nearly all will one day be released. Consider Tore (not his real name), an inmate at Bastoy. He spent his 20s selling drugs, drinking and partying. One day, when he was high on methamphetamine and had not slept for three days, he attacked two friends with a knife, over nothing—some expensive clothes. He was arrested, charged and got into another fight while awaiting trial. He was eventually given a 14-year sentence for three attempted murders and intending to sell several kilos of hash.

For the first couple of years inside a closed prison, he was furious and blamed “everyone else” for his plight, he says. But then he took a course with a counsellor who had lived “the same life”. She talked to him about his regret for what he had done, and persuaded him that he could never touch alcohol again. It took many months. “It was like freedom,” he recalls.

At Bastoy he took a carpentry exam. He will probably be released in three years. On that day, he expects to have a job. Bastoy inmates can start working outside 18 months before they are released—the aim is to ensure that every ex-prisoner has a roof, an income and something to do. (In America some prisoners are released after long sentences with little more than clothes and a bus fare.) Eventually Tore plans to set up his own carpentry business.

Prisons around the world use a variety of tools to prevent recidivism. It is fiendishly hard to disentangle what influences a convict’s future behaviour, but Adam Gelb of the Pew Charitable Trusts, a think-tank, lays out some principles which have been shown to work.

First, identify the inmates who are most likely to reoffend. Some good predictors of this cannot be changed, such as a troubled family background and previous criminal history. Age is also crucial—some 68% of federal prisoners in America who are released before the age of 21 are rearrested within 8 years; for the over-60s, it is only 16%. Other risk factors are more malleable. Poor impulse control, substance abuse and the habit of picking anti-social friends can all respond to treatment.

Rehabilitation programmes that focus on factors other than crime, such as creative abilities, physical conditioning and self-esteem do not reduce criminal behaviour, argues Edward Latessa of the University of Cincinnati. Boot camps are especially ineffective: they foster aggression and bond criminals together.

Oliver Bueno, a former drug-dealer, agrees. “I came out worse,” he recalls of his time in a juvenile boot camp in Nevada. “You got beat up all the time by staff,” he says, adding that the guards were “ex-military, hillbillies and real racists”. He describes having his head shaved and being constantly shouted at. “The abuse got me more and more angry, hating authority,” he says. After his release, he went straight back to gangbanging, selling drugs and getting into fights over trivial slights. Shortly before his next arrest, he says, “I had a gun in [another man’s] face and I don’t even remember what it was about.”

Perhaps the best tool is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). This is not about sitting in a circle and sharing one’s inner demons. It is about helping people to understand the “triggers”—people, places and things—that prompt them to offend. The counsellor nudges the offender towards minimising negative influences and maximising positive ones. For example, “If you get together with your friend Tom on payday and go crazy, maybe you should avoid Tom on payday,” says Mr Gelb. Counsellors should not argue or hector, but show that they are listening and praise offenders for acting responsibly.

Norway uses CBT a lot—Tore benefited from it. America uses it spottily. A study of over 500 programmes in American prisons, jails and probation agencies by Faye Taxman of George Mason University found that only 20% involved CBT and only about 5% of individuals were likely to have access to it. Done well, it can reduce recidivism by 10-30%. A meta-analysis of 50 CBT programmes in America by Thomas Feucht and Tammy Holt for the National Institute of Justice, a government body, found that 74% were effective or promising. They worked best with juvenile offenders and worst with wife-beaters. There was mixed evidence for the effect on sex offenders, who are hard to reform.

The great escape

Mr Bueno, the former drug-dealer, says he was reformed not by anything he learned in prison, but by Hope for Prisoners, a charity—and God. When he left his cell for the final time, he went back to his old friends and was “walking back down the same old paths”. Then his girlfriend (now wife) suggested he go and listen to Jon Ponder, an armed robber-turned-preacher, who teaches ex-convicts to take responsibility for their lives. Mr Bueno exults that he has joined “the most powerful gang in the world—God’s gang”. Tore, in Norway, has a more secular view of reform: “I just want to be a normal person and pay tax.”