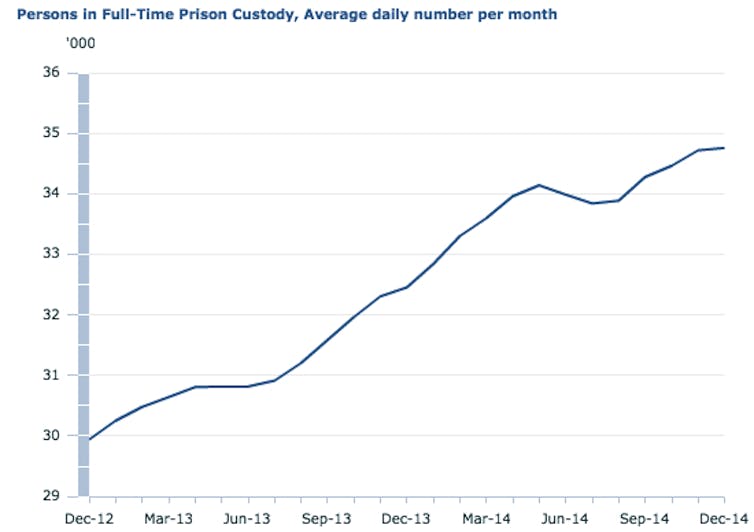

Australia has reached a decade-high rate of imprisonment. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ announcement of this last year created little impact or interest.

Across Australia, 33,791 persons were in adult corrective services custody at June 30 2014. That was a 10% increase from 2013. By the December quarter 2014, the average daily number of prisoners had risen to 34,647.

For both men and women in custody, the most frequent serious offence was an act intended to cause injury (21% for men, 20% for women).

The next most common offences differed according to gender. Men were equally likely to be in custody for a most serious offence of sexual assault, unlawful entry with intent and illicit drug offences (all 12%). For women, the next most likely reasons were illicit drug offences (17%) and offences against justice procedures, government security and operations (11%).

The circumstances that lead to imprisonment and the context of the crime cannot be ascertained from such data. It still raises important questions about the use of imprisonment for non-violent offences.

Indigenous Australians suffer punitive approach

An ongoing issue in Australia, which we have failed to reverse – just as we have failed to close the gap – is the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in our prisons.

Nationally, the rate of imprisonment for ATSI people was 13 times higher than for non-Indigenous people at June 30, 2014. This figure covers a diverse situation across the nation. In Western Australia, ATSI men and women are 18 times more times likely than non-Indigenous Australians to be imprisoned in WA, whereas in Tasmania the rate is four times higher.

In 2013, Chris Cunneen articulated the concern in The Conversation that:

… too many Indigenous Australians will remain second-class citizens in their own country … remaining the object of law when it comes to criminalisation and incarceration.

The most recent statistics affirm that Cunneen’s predictions are unfolding with little sign of abating.

Prisons are a poor substitute for mental health care

An emerging concern is the recognition and realisation that mental illness and mental impairment are diagnosed at much higher rates within our imprisoned population than in the wider community.

Data on this issue is less easily accessed nationally. What we do know is that there is a “higher incidence of mental health problems in the Australian prison population than in the general population” and that “almost two in five prison entrants (38%) reported having been told that they have a mental health disorder”.

Prison is fast becoming a significant location for individuals with high mental health needs to be supported and managed. This reflects a national malaise, stemming from the responsibility we must all bear for decisions to remove so many of the support networks that were in place decades ago – and to remove them without any replacement or alternative. The result has been the criminalisation of an increasing number of people.

Public debate ignores need for change

This brief review of current data and trends raises several important questions: why is imprisonment being used, for what purpose, and to what ends?

This series aims to offer a snapshot of incarceration trends across Australia and to identify imprisonment policies and practices that we need to change.

Each state and territory has different issues of most concern. These may relate to rates of imprisonment of particular marginalised populations, or legislative changes resulting in remand rates skyrocketing and/or parole being virtually unobtainable.

While Australian trends in imprisonment can always be favourably compared to other nations such as the US, it is clear that current trends across the nation have significant short-and long-term consequences. Attracting public attention and engagement with these consequences is challenging in a political, social, and media environment dominated by law-and-order politics.

This series aims to provide a platform for public discussion via a critical mass of articles that take stock of the situation in each state and territory, and as a nation.

You can read other articles in the series here.