As one of the two original Australian convict colonies, Tasmania shares with New South Wales an ignominious history of capital punishment in the first half century of settlement.

The Prosecution Project has recently completed an inventory of executions carried out in Tasmania, beginning in the year 1806 and extending to the last in 1946. This is a painstaking exercise since there is no single source accounting for all the executions that took place. But our data now suggests that there were a total of 545 executions out of the 1469 death sentences handed down by courts in Tasmania over that period. Not all the executions took place in Tasmania itself. Prior to 1824 when the Supreme Court was established, at least 15 were tried in Sydney though executed in Tasmania. The Tasmanian data also includes the death sentences carried out at Norfolk Island, 37 of them during the convict years.

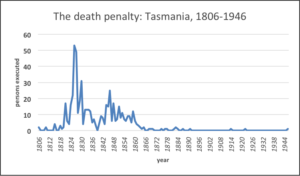

By the 20th century the legal system, government policy and public sentiment had combined to diminish drastically the use of the death penalty in Tasmania. Only three people were executed as a result of a judicial sentence during the twentieth century. The frequency of executions had been steadily falling since the 1850s. As our graph shows there was a final flurry of executions around 1860, no less than 12 being sent to the gallows in 1859. But the historical record suggests that 90% of death sentences carried out in Tasmania occurred in the period before self-government.

It is well-known that the British settlers brought with them a capital code, used intensively in the first few decades of the 19th century. It was not till the late 1830s that statutory reform reduced the number of offences for which a death sentence might be awarded. In Australia the colonies did not adopt the imperial model fully, for example retaining the death penalty for rape well into the 20th century in some states. But after 1837, for example, the penalty for conviction on the common charge of housebreaking (breaking into a house and stealing) was no longer death.

Another important mitigation of the death penalty was contained in the provision for the sentence of ‘death recorded’, enabled by an English law reform in 1823. This was a discretionary provision, most commonly applied in cases of property offence, more rarely in cases of non-homicidal offences against the person. Some indicator of increasing leniency in judicial sentencing is evident in the fact that while less than a quarter of sentences in the earlier decades were ‘death recorded’, this penalty benefited almost a third of those convicted of a capital offence after 1837. A little more common was the post-sentence exercise of clemency, with death sentences being commuted to life imprisonment or transportation. And a few even benefited from an executive pardon, after post-conviction information was brought to the notice of the attorney-general.

The effect of the legal changes in the 1830s is reflected in the pattern of sentences for which people were hanged before and after 1837. Prior to that date it was not murder but a variety of property offences that were most likely to bring an offender to the gallows. Not so serious offences of stealing and receiving accounted for more than a quarter of executions before 1837 and the more serious property offences of robbery and its colonial variant bushranging accounted for another third. Robbery remained a serious and capital offence after 1837 but accounted for only about one in six of the 256 executions that took place after that date. The effect of law reform was to accentuate offences against the person as the most serious criminal offences. And so two-thirds of executions after 1837 were for a homicide offence, and one in 10 for a sex offence.

Together, Tasmania and New South Wales executed their sentenced prisoners in numbers to rival those so punished in Britain in the 1820s and 1830s. These were decades preceding the effect of law reform that reduced the number of offences liable to the death penalty. Local government policy directed to the control of a convict population and its ancillary challenges, especially bushranging, help to explain the drastic use of the death penalty. In Tasmania policy seemed especially harsh – a greater proportion of those sentenced to hang in the convict colony during the after years were more likely to end their lives in this way than in New South Wales. For both places, the convict legacy in historical memory remains one of harsh but also, as this data shows, commonly mitigated punishment.

Authors: Mark Finnane and Chris Leppard

Further reading: Richard Davis, 1974. The Tasmanian Gallows: A Study of Capital Punishment. Hobart: Cat & Fiddle Press; Steve Harris, 2015. Solomon’s Noose: The True Story of Her Majesty’s Hangman of Hobart Town. Melbourne: Melbourne Books; Tim Castle, 2008. “Watching Them Hang: Capital Punishment and Public Support in Colonial New South Wales, 1826-1836.” History Australia 5 (2): 43.1-43.15. https://doi.org/10.2104/ha080043.

To cite this research brief: Mark Finnane and Chris Leppard, ‘The hanging years’ The Prosecution Project, Research Brief 30, https://prosecutionproject.griffith.edu.au/why-we-need-lawyers/ (9 Apr 2018, viewed 28 Apr 2018).