Credit-Card Companies Know How Little You Know

When I was 22, I wondered how credit-card companies made money. I had two cards at the time. They were free to use. Every month I would buy things with the cards, and -- because I used auto-pay -- every month the balance would be deducted from my checking account. As far as I could tell, this was a free service. And if I decided not to pay my credit-card bills, and just go bankrupt, there was no way the card issuer would make money off of me. With things like cash back, it seemed like I was getting paid to use this card. What kind of business model pays people to use its product?

Ten years later, as I helped a friend figure out how to refinance his credit-card bills, I realized how the business model must work. Card issuers, mainly banks, profit by charging penalty fees when people pay off their credit-card balances late. Of course, that isn't the only way they make money -- they, along with MasterCard and Visa, also charge merchants fees to use the payment services, and they charge other fees for things like balance transfers. But a lot of their business model is just consumer lending -- which they do at rates of about 12 percent to 14 percent.

Now, why would a consumer take out a loan at rates like that? If you’re buying a house, you would get a mortgage at a rate of about 3.5 percent. If you’re buying a car, you’d get an auto loan, which are at more like 1 percent to 3 percent. Items like furniture and electronics cost much less, so it seems pretty easy to save up money to buy these things most of the time. Maybe you spend more than you can pay off right away if you just got your first job and you need to use credit cards to furnish your apartment -- but that isn't an everyday event.

The only reasonable, routine use I can think of for credit cards where you don't pay off the balance is medical expenses. These come on suddenly and can be big, even with health insurance. This was my friend’s reason for running up credit-card debt, and he’s not alone -- in 2012, a New York Times survey found that the average low-to-moderate income household had more than $1,600 in credit-card debt from medical bills.

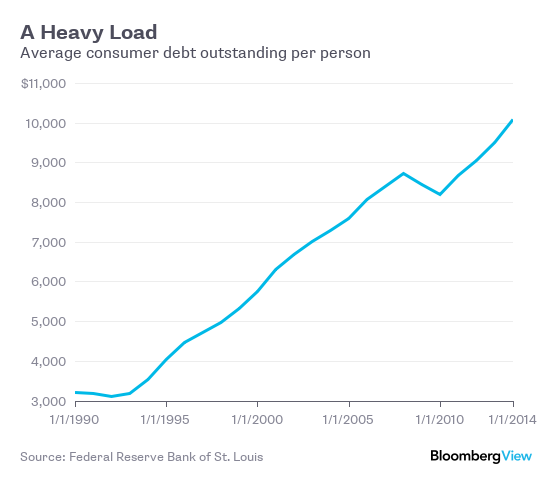

Yet the amount of credit-card debt in the U.S. far exceeds that number. Here’s the average outstanding consumer debt per person, most of it from credit cards:

Basically, that means there are a lot of people out there who buy things with credit cards, and who then either can’t or won’t pay for those things at the end of the month, and who instead decide to make payments on the debt each month. At 12 percent or 14 percent interest that’s a very expensive way to live. But some people do it.

Why? Well, you won’t find much of an explanation in the school of economics that assumes everyone is rational and where people only borrow when it makes economic sense to do so. But behavioral finance is replete with examples of short-sightedness, lack of self-control and over-optimism about one’s future. These behavioral biases might not afflict everyone, but lots of people are certainly vulnerable -- especially the poor and less educated.

Credit-card companies need people to spend more than they can afford, but not so much that they default on their payments. So they could benefit from targeting individuals who are more likely to have cognitive failings. This is the dark side of behavioral finance.

Some new research by economists Antoinette Schoar of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Hong Ru of Nanyang Technological University claims to find exactly such a result. The authors use data from a private company that tracks credit-card offers. They find that less educated consumers -- who are likely to be less financially sophisticated -- are more frequently given offers that include back-loaded costs. Those are plans that start with low rates, but increase later, with extra-high over-limit and late-payment fees. In other words, those are likely to be the borrowers who make bad financial decisions -- racking up debt and eventually paying much more in interest. Meanwhile, more educated households tend not to be offered these plans.

So my 22-year-old intuition was sort of right. In a rational world, where people pay high interest rates only when they absolutely need to, credit-card issuers have a harder time making money. They still have merchant fees, of course, but without the ability to exploit people’s financial miscalculations, they wouldn’t be so consistently profitable.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Noah Smith at nsmith150@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net