Summary of Australian Indigenous health

This Summary of Australian Indigenous health provides a plain language summary of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, with brief information about the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, health problems and common risk factors.

Introduction

This summary includes the following information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples:

- population

- births

- deaths

- common health problems

- health risk and protective factors.

This summary uses information from the most up-to-date sources to help create a picture of the health of Australia’s Indigenous people. This report uses four main sources of information:

- reports in the Health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples series produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW)

- the Indigenous compendium to the Report on government services produced by the Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision (SCRGSP)

- reports on key indicators of Indigenous disadvantage also produced by SCRGSP

- reports in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework series produced by the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council for the Department of Health and Ageing.

Data for these reports are collected through health surveys, by hospitals, and by doctors across Australia.

An important issue when collecting health information or data is to make sure the information is accurate and reliable. If some details are missing the information may not be accurate. For example, to understand data about Indigenous people, states and territories need to collect information about their patients, including whether a person is Indigenous. Some states and territories (like SA, WA and the NT) reliably collect this information, but others (like the ACT and Tas) do not. This means that most information about the health of Indigenous people is only accurate for certain states and territories, but not for Australia as a whole. The information about the Indigenous population is getting better, but there are still limitations. To get a more detailed picture of Indigenous health (which includes details of the coverage of each health topic by states/territories), please refer to our Overview of Australian Indigenous health status(http://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/overviews).

To create a complete picture, all the information in this report should be looked at in the context of the 'social determinants of health', the term used to talk about factors that affect people's lives, including their health [1][2][3].

The social determinants of health include if a person:

- is working

- feels safe in their community (no discrimination)

- has a good education

- has enough money

- feels connected to friends and family.

Social determinants that are particularly important to many Indigenous people are:

- their connection to land

- the historical past that took people from their traditional lands and away from their families.

If a person feels safe, has a job that earns enough money, and feels connected to their family and friends, they will generally be healthier. Indigenous people are generally worse off than non-Indigenous people when it comes to the social determinants of health [1].

A lot of health services are not as accessible and user-friendly for Indigenous people as they are for non-Indigenous people, adding to higher levels of disadvantage. Sometimes this is because more Indigenous people than non-Indigenous live in remote locations and not all health services are offered outside of cities. Sometimes health services are not culturally appropriate (do not consider Indigenous culture and the specific needs of Indigenous people). Also, some Indigenous people may not be able to use some services because they are too expensive.

What makes health services more accessible for Indigenous people?:

- having Indigenous Health Workers on staff

- increasing the number of Indigenous people working in the health sector (doctors, dentists, nurses, etc)

- designing health promotion campaigns especially for Indigenous people

- having culturally competent non-Indigenous staff

- making important health services available in rural and remote locations (so Indigenous people living in rural and remote areas do not have to travel to cities, away from their support networks)

- funding health services so they are affordable for Indigenous people who might otherwise not be able to afford them.

More detailed information about the health of Indigenous peoples, associated social and economic circumstances, and risk and protective factors, is available from the HealthInfoNet’s web resource (www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au).

What is known about the Indigenous population?

Based on information from the 2011 Census, the ABS estimates that there were 669,736 Indigenous people living in Australia in 2011 [4]. NSW had the largest number of Indigenous people, and the NT had the highest percentage of Indigenous people. Indigenous people made up 3.0% of the total Australian population. For more details on the Indigenous population in each state and territory see the table below.

| State/territory | Number of Indigenous people | Proportion (%) of Indigenous population living in that state/territory | Proportion (%) of state/territory population that are Indigenous |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: ABS, 2012 [4] | |||

| NSW | 208,364 | 31.1 | 2.9 |

| Vic | 47,327 | 7.1 | 0.9 |

| Qld | 188,892 | 28.2 | 4.2 |

| WA | 88,277 | 13.2 | 3.8 |

| SA | 37,392 | 5.6 | 2.3 |

| Tas | 24,155 | 3.6 | 4.7 |

| ACT | 6,167 | 0.9 | 1.7 |

| NT | 68,901 | 10.3 | 29.8 |

| Australia | 669,736 | 100.0 | 3.0 |

The number of Indigenous people counted in the 2011 Census was much higher than the number counted in the 2006 Census [5]. This could be explained by a number of factors:

- the number of Indigenous people has increased

- more Indigenous people were counted because of improvements in how the Census was conducted

- more Indigenous people identified as Indigenous in their response.

In 2011, 90% of Indigenous people identified as Aboriginal, 6% identified as Torres Strait Islanders, and 4% identified as both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander [6].

In 2011, around one-third of Indigenous people lived in major cities [6].

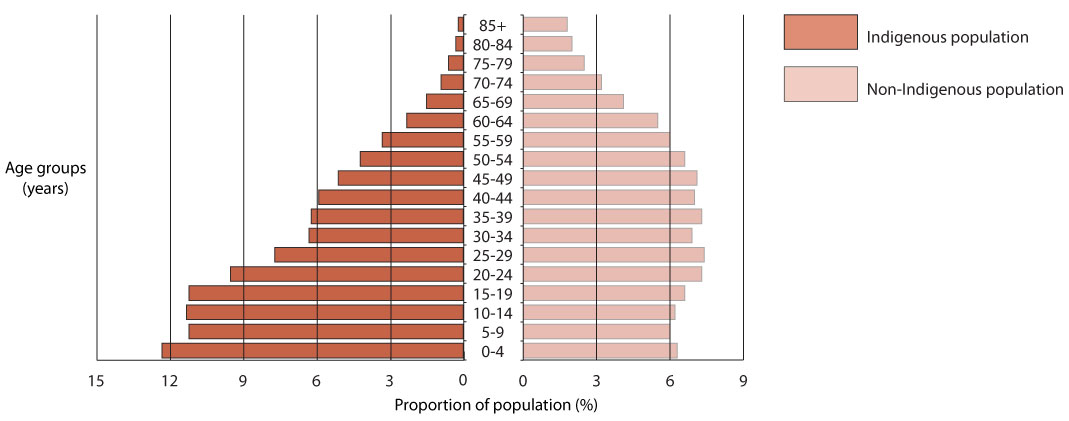

The Indigenous population is much younger overall than the non-Indigenous population [4]. In 2011, more than one-third of Indigenous people were aged less than 15 years, compared with one-fifth of non-Indigenous people [7][8]. Almost 4% of Indigenous people were aged 65 years or over, compared with 14% of non-Indigenous people. Figure 1 shows a comparison of the age profiles of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations.

Figure 1. Population pyramid of Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, 2011

What is known about Indigenous births?

In 2011, there were 17,621 births registered in Australia where one or both parents were Indigenous (six out of every 100 births) [9]. Overall, Indigenous women had more children and had them at younger ages than did non-Indigenous women.

Indigenous women had, on average, 2.7 births in their lifetime (compared with 1.9 births for all Australian women) [9]. Around three-quarters of Indigenous mothers were 30 years or younger when they had their babies, compared with less than one-half of all mothers. About 19 in 100 Indigenous mothers were teenagers, compared with 4 in 100 of all Australian mothers.

In 2010, babies born to Indigenous women on average weighed almost 200 grams less than those born to non-Indigenous women [10]. Babies born to Indigenous women were twice as likely to be of low birthweight (less than 2,500 grams) than were those born to non-Indigenous women. Low birthweight can increase the risk of a child developing health problems.

One way of looking at how common a disease is in a population is by calculating a ‘rate‘. A rate is the number of cases of a disease divided by the population, for a specific amount of time. By calculating rates, you can compare how common a disease is in different populations (like Indigenous and non-Indigenous people) or between sexes (men and women). You can also calculate rates for deaths, which lets you compare the number of deaths in two different populations.

There is a special calculation for ‘infant mortality rates‘. To calculate this rate, the number of infants (children under one year of age) who died in one calendar year is divided by the number of live births in the same year.

What is known about Indigenous deaths?

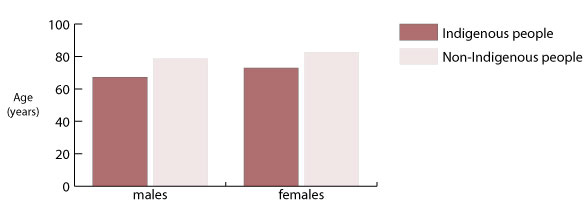

Indigenous people are much more likely than non-Indigenous people to die before they are old [11][12]. The most recent estimates from the ABS show that an Indigenous male born in 2005-2007 was likely to live to 67.2 years, about 11.5 years less than a non-Indigenous male (who could expect to live to 78.7 years) (Figure 2) [11]. An Indigenous female born in 2005-2007 was likely to live to 72.9 years, which is almost 10 years less than a non-Indigenous woman (82.6 years). (In 2010, the ABS changed the way it calculates Indigenous life expectancy, so recent estimates cannot be compared with older estimates.)

Figure 2. Expectations of life at birth for Indigenous and non-Indigenous males and females 2005-2007

In 2011, there were 2,558 deaths registered to people identified as Indigenous [12]. Many Indigenous deaths are incorrectly counted as non-Indigenous because the person or family are not identified as Indigenous – the actual number of Indigenous deaths is not known, but would be higher than the number registered.

The leading causes of death in 2006-2010 for Indigenous people were:

- cardiovascular disease (including heart attacks and strokes)

- cancer

- injury (including transport accidents and self-harm) [13].

Babies born to Indigenous women are more likely to die in their first year than those born to non-Indigenous women [12]. In 2009-2011, the infant mortality rate (see boxed information for details) for babies born to Indigenous women was highest in the NT (around 13 babies died for every 1,000 births) and lowest in NSW (less than five babies died for every 1,000 births). The rate for the total Australian population was around four deaths for every 1,000 births in 2011.

Specific health conditions

What is known about heart health in the Indigenous population?

Many Indigenous people are affected by cardiovascular disease (CVD), a group of diseases affecting the heart and circulatory system [14]. The most common types of CVD are coronary heart disease (including heart attack), stroke, heart failure, and high blood pressure. Risk factors (a behaviour or characteristic that makes it more likely for a person to get a disease) for CVD include: smoking tobacco, not eating well, and having diabetes.

In the 2004-2005 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS), almost one-in-eight Indigenous people reported having a long-term heart or related condition [15]. Heart and related conditions were around 1.3 times more common for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people; high blood pressure (the most commonly reported condition) was reported 1.5 times more often by Indigenous people than by non-Indigenous people.

CVD was the most common cause of death for Indigenous people in 2006-2010 [13]. More than one-quarter of Indigenous deaths were from CVD. Deaths from CVD happened almost twice as often for Indigenous people as for non-Indigenous people. Indigenous people were much more likely to die from CVD than other Australians at any age, but particularly in younger age-groups [16].

In 2006-2010, coronary heart disease caused more than one-half of CVD-related deaths; heart attacks were responsible for one-in-five CVD-related deaths [13]. Strokes caused around one-in-nine deaths from CVD of Indigenous men and around one-in-six of those of Indigenous women.

What is known about cancer in the Indigenous population?

Cancer is a disease of the body's cells (the basic building blocks of the body) [17]. Normally cells multiply and grow in an ordered way, but sometimes the genetic blueprint (DNA) of cells is damaged and uncontrolled growth can occur; this is cancer. Cancer can occur almost anywhere in the body. Cancer cells are ‘benign’ if they do not spread into surrounding areas or to different parts of the body, and are not generally dangerous. If cancer cells spread into surrounding areas, or to different parts of the body (metastasise), they are known as ‘malignant’. Malignant cancers can cause illness and death.

In 2004-2008, the overall rate of new cases (incidence rate) of cancer was slightly higher for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people [18]. Incidence rates vary depending on the type of cancer. Indigenous people had higher incidence rates than did non-Indigenous people in 2004-2008 for:

- lung and other smoking-related cancers

- cervical cancer (for women)

- cancer of the pancreas

- cancers of ‘unknown primary site’ (the part of the body where the cancer started) [19].

Indigenous people had lower incidence rates than did non-Indigenous people in 2004-2008 for:

- breast cancer (for women)

- prostate cancer (for men)

- bowel cancer

- non-Hodgkin lymphoma (the lymphoid system is part of the body’s immune system, the system that helps the body ward off diseases)

- melanoma (skin cancer that occurs in the pigment cells) [19].

In 2006-2010, cancer was the second most common cause of death for Indigenous people [18]. The types of cancer that caused the most deaths among Indigenous people were lung cancer, cancer of ‘unknown primary site’, breast cancer (for women), and bowel cancer [19]. The likelihood of getting lung cancer increases when people smoke tobacco.

The fact that Indigenous people are more likely than non-Indigenous people to die from cancer could be because:

- the types of cancers they develop (such as cancers of the lung and liver) are more likely to be fatal

- their cancer may be more advanced by the time it is found (which is partly because Indigenous people may visit their doctor later and/or may not participate in screening programs)

- they are less likely to receive adequate treatment [20].

What is known about diabetes in the Indigenous population?

Diabetes is a condition where the body cannot properly process glucose (a type of sugar) [21]. Normally the body can convert glucose into energy with the help of a hormone called insulin. If someone has diabetes, their body’s production of insulin is impaired. Without enough insulin the body cannot turn glucose into energy, and it stays in the blood. The treatment of diabetes depends on the type of diabetes that a person has – if someone has type 1 diabetes they will need insulin injections; if someone has type 2 diabetes they may be able to manage it by living a healthy lifestyle or taking some medicines. It is possible for a person to have type 2 diabetes without knowing it.

Diabetes is a major health problem for Indigenous people, but it is hard to know just how many Indigenous people have the disease. Diabetes was reported by 6% of Indigenous people in the 2004-2005 NATSIHS [15]. However, it is believed that only around one-half of Indigenous people with diabetes actually know they have it, so it has been estimated that between 10% and 30% of Indigenous people may have the condition [22][23].

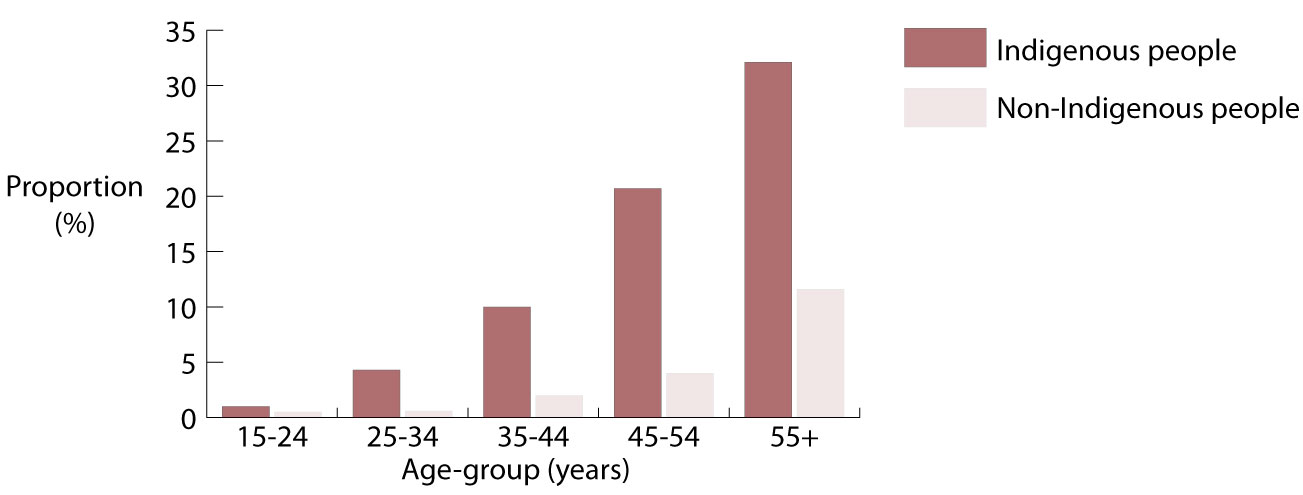

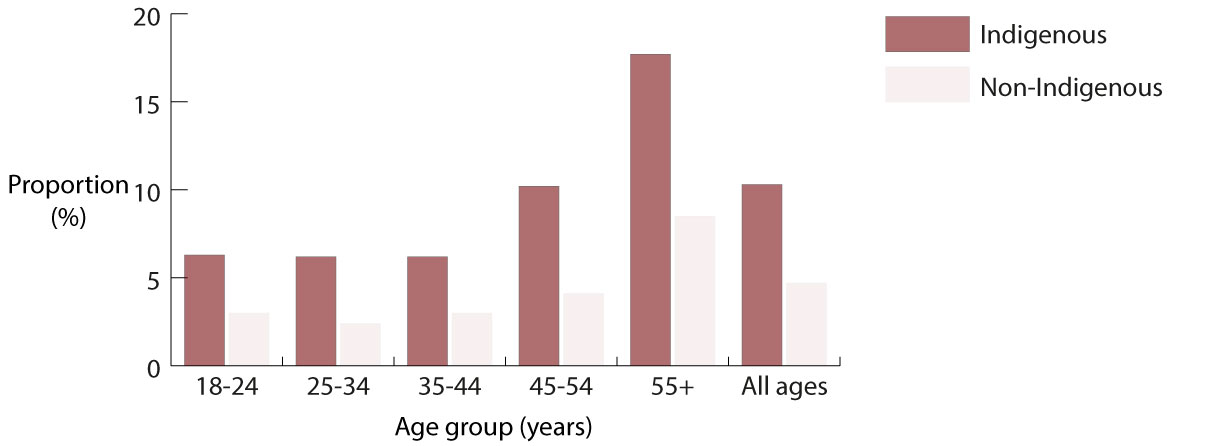

According to the 2004-2005 NATSIHS, diabetes was more common for Indigenous people living in remote areas (9%) than for those living in non-remote areas (5%) [15]. Diabetes affects Indigenous people at a younger age than non-Indigenous people – it affects high numbers of Indigenous people over the age of 25 years, which is earlier than for non-Indigenous people (Figure 3). Overall, diabetes is more than three times more common among Indigenous people than among other Australians.

Deaths from diabetes were seven times more common for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people in 2006-2010[13].

Figure 3. Proportions (%) of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people reporting diabetes as a long-term health condition, by age-group (years) 2004-2005

What is known about the social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous people?

Social and emotional wellbeing is a term used to talk about a person’s overall social, emotional, psychological (mental), spiritual, and cultural wellbeing. Factors that are important to social and emotional wellbeing include a person’s:

- connection to land

- ancestry (family history)

- relationships with family members and friends

- connection to community [24].

Social and emotional wellbeing is often confused with mental health, but it is much broader: social and emotional wellbeing is concerned with the overall wellbeing of the person. On the other hand, mental health describes how a person thinks and feels, and how they cope with and take part in everyday life. It is often seen, incorrectly, as simply the absence of a mental illness.

Many things can influence a person’s social and emotional wellbeing, including:

- historical/past events

- serious illness or disability

- death of family members or friends

- substance and/or alcohol use

- social and economic factors (education, employment, income, housing) [16][24].

Measuring social and emotional wellbeing is difficult, but it usually relies on self-reported feelings (like happiness or calmness) or ‘stressors’ (stressful events in a person’s life).

The 2008 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) collected information on positive wellbeing and asked people to report on feelings of happiness, calmness and peacefulness, fullness of life, and energy levels. The survey found that most (nine-out-of-ten) Indigenous people felt happy some, most, or all of the time [25]. Around four-out-of-five Indigenous people reported feeling calm and peaceful, full of life, and that they had a lot of energy some, most, or all of the time.

Similar information has not been collected from non-Indigenous people, so there is no way to compare Indigenous and non-Indigenous people's positive wellbeing. It is likely, however, that Indigenous people would report lower levels of social and emotional wellbeing overall because they experience higher levels of psychological distress and more stressors when compared with non-Indigenous people [16][26].

The 2008 NATSISS and the 2007-2008 National Health Survey (NHS) found that Indigenous adults were two-and-a-half times more likely to feel high or very high levels of psychological distress than were non-Indigenous adults [25].

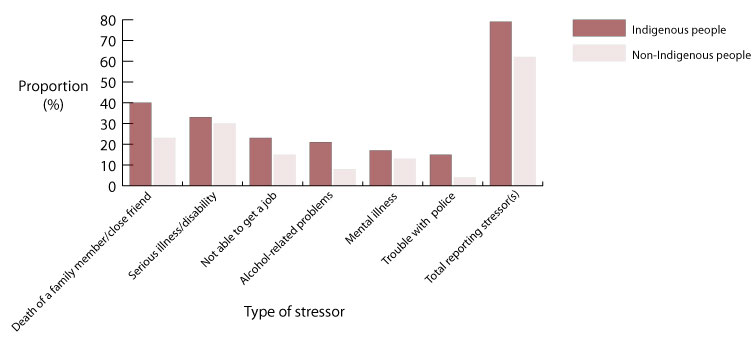

Indigenous people may have higher levels of psychological distress because they experience more stressors than do non-Indigenous people. The 2008 NATSISS found that almost eight-out-of-ten Indigenous people experienced one or more significant stressors in the year before the survey interview [16]; this compared with six-out-of-ten for the total population[26].

Compared with the stressors reported by the general population in the 2010 General Social Survey (GSS), many more Indigenous people reported stressors like: the death of a family member or friend; alcohol or drug related problems; trouble with the police; and witness to violence (Figure 4) [16]. Almost one-in-five Indigenous people also reported that either themselves, a family member, or friend had been sent to jail in the previous 12 months, but this stressor was not reported by the general population.

Figure 4. Proportion (%) of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people who experienced stressor(s), by type of stressor, 2008 and 2010

In 2010-11, Indigenous people were more than twice as likely to be hospitalised for ‘mental and behavioural disorders’ than were other Australians (‘mental and behavioural disorders’ occur when a person becomes unwell in the mind and experiences changes in their thinking, feelings, and/or behaviour that affects their day-to-day life) [27].

In 2005-2009, there were 268 Indigenous deaths from ‘mental and behavioural disorders’ [25]. Compared with the non-Indigenous population, Indigenous people were nearly twice as likely to die from these disorders.

Deaths from ‘mental and behavioural disorders’ do not include deaths from ‘intentional self-harm’ (suicide). In 2010, Indigenous people were two-and-a-half times more likely to die from ‘intentional self-harm’ than were non-Indigenous people [28]. Deaths from intentional self-harm are especially high for Indigenous people aged 34 years or younger, with Indigenous males at a very high risk of death from ‘intentional self-harm’.

The most detailed information on the social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous children comes from the Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey (WAACHS). This survey found that almost one-quarter of Indigenous children and young people were rated by their carer (parent or guardian) as being at high risk of ‘clinically significant emotional or behavioural difficulties’ (emotional or behavioural problems that affect a person's day-to-day life); this compares with one-in-seven children for the general WA population [29].

Indigenous children whose carers had been forcibly separated (taken away) from their families were at high risk of having ‘clinically significant emotional or behavioural difficulties’, more than twice the risk of children whose carer had not been forcibly separated [29]. These children also had twice the rates of alcohol and other drug use.

The WAACHS also found that seven-out-of-ten Indigenous children were living in families that had experienced three or more major life stress events (like a death in the family, serious illness, family breakdown, financial problems, or arrest) in the year before the survey, and one-in-five had experienced seven or more major stress events [29].

What is known about kidney health in the Indigenous population?

Healthy kidneys help the body by removing waste and extra water, and keeping the blood clean and chemically balanced[30]. When the kidneys stop working properly – as is the case when someone has kidney disease – ‘waste’ can build up in the blood and damage the body. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is when the kidneys gradually stop working [31]. End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is when the kidneys have totally or almost totally stopped working. People with ESKD must either have regular dialysis (be hooked up to a machine that filters the blood) or have a kidney transplant to stay alive.

Kidney disease is a serious health problem for many Indigenous people. In 2006-2010, ESKD was seven times more common for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people (Derived from [32][33][34][35]).

ESKD affects Indigenous people when they are much younger than it does among non-Indigenous people. Almost two-thirds of Indigenous people diagnosed with ESKD in 2006-2010 were younger than 55 years of age (less than one-third of non-Indigenous people were younger than 55 years of age) (Figure 5) (Derived from [32][33][34][35]).

The rates of ESKD were highest for Indigenous people living in the NT (20 times higher for Indigenous people than non-Indigenous people) and WA (11 times higher) (Derived from [32][33][34][35]).

Figure 5. Rates (per million) of end-stage kidney disease for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, by age-group (years) 2006-2010

Dialysis was the most common reason for Indigenous people to be admitted to hospital in 2010-11 [27]. Almost one-half of all Indigenous hospital admissions were for dialysis. Indigenous people were admitted to hospital for dialysis around 11 times more often than were other Australians.

Some people need to have dialysis every day. Dialysis can be undertaken at hospitals, special out-of-hospital satellite units, or in the home (which requires special equipment and training for the patient and their carer(s), and is very costly)[36]. Accessing dialysis can sometimes be very difficult for Indigenous people who live in rural or remote locations and they may have to travel to receive treatment.

In 2006-2010, Indigenous people were four times more likely to die from kidney disease than were non-Indigenous people[13].

What is known about injury in the Indigenous population?

Injury generally refers to physical harm to a person's body [37] including:

- assault

- self-harm

- environmental injuries (e.g. being bitten by a dog or being poisoned by inhaling poisonous fumes)

- transport accidents [38].

Culture and everyday life situations for Indigenous people can affect the types of injuries and the frequency of injuries experienced. Some factors that can increase the risk of injury include:

- disruption to culture

- socioeconomic disadvantage [38]

- living in rural and remote locations (including increased use of roads)

- risky behaviour

- limited access to health services and support services [39].

Indigenous people were twice as likely as other Australians to be admitted to hospital for injuries in 2010-11 [27]. Injury was the second most common reason for Indigenous hospital admissions (after dialysis). The main causes of Indigenous injury-related hospital admissions in 2010-11 were 'medical complications', assault, and falls [40].

In 2010, injury was the third most common cause of death for Indigenous people [41]. The most common causes of injury-related death for Indigenous people were suicide and transport accidents. Indigenous people were more than twice as likely as non-Indigenous people to die from suicide and almost three times as likely to die from traffic accidents.

What is known about respiratory health in the Indigenous population?

The respiratory system includes all the parts of the body involved with breathing, including the nose, throat, larynx (voice box), trachea (windpipe), and lungs [42]. Respiratory disease occurs if any of these parts of the body are damaged or diseased and breathing is affected. Common types of respiratory disease include colds and similar viral infections, asthma and pneumonia.

Risk factors for respiratory disease include: infections, smoking (including passive smoking, which is particularly bad for children), poor environmental conditions (especially areas that are dusty or have lots of pollen or pollution), poor living conditions, and other diseases (like diabetes, heart and kidney disease) [42].

Respiratory disease was reported by around one-quarter of Indigenous people in the 2004-2005 NATSIHS [15]. Respiratory problems were reported more often by Indigenous people living in non-remote areas (nearly one-third) than by those living in remote areas (nearly one-fifth).

Indigenous and non-Indigenous people had similar levels of most kinds of respiratory disease, but asthma (the condition most often reported by Indigenous people) was 1.6 times more common for Indigenous people in 2004-2005 [15].

In 2010-11, more than one-in-ten of all hospital admissions for Indigenous people were because of a respiratory condition (excluding hospital admissions for dialysis) [40]. Indigenous people were almost three times more likely than other Australians to be admitted into hospital for a respiratory condition.

In 2010, respiratory disease was the cause of 8% of Indigenous deaths [41]. Indigenous people were more than twice as likely as other Australians to die from a respiratory disease.

What is known about eye health in the Indigenous population?

Having healthy eyes is important for everyday life; they are needed to read and study, play sports, drive, and work [43]. There are a number of problems that can affect the health of the eye [44]. The most common conditions are:

- refractive error (problems focussing the eyes)

- cataract (clouding of the eyes’ lenses)

- diabetic retinopathy (caused by diabetes and can lead to blindness)

- infectious diseases like trachoma.

Eye problems are associated with: getting older, smoking, injuries, exposure to ultra-violet (UV) light from the sun, and not eating enough healthy food [44]. Eye health problems can result in low vision (not being able to see properly). This can be corrected with glasses, contact lenses or eye surgery. Eye health problems can result in impaired eyesight and blindness.

Many Indigenous people do not have access to specialised eye health services, including optometrists and ophthalmologists (specialist eye doctors) [45]. As a result, Indigenous people are more likely than non-Indigenous people to suffer from poor eye health that is preventable. In the 2004-2005 NATSIHS, eye and/or sight problems were reported by almost one-third of Indigenous people [15].

The 2008 National Indigenous Eye Health Survey (NIEHS) found that low vision was nearly three times more common for Indigenous adults than for other Australian adults [46]. Overall, 3% of Indigenous adults suffered vision loss caused by cataracts, but only 65% of Indigenous people who needed cataract surgery received it. Refractive error caused one-half of vision loss in both adults and children.

Diabetes, a major problem for Indigenous people, can cause eye disease and loss of vision. The 2008 NIEHS found that only one-in-five Indigenous people with diabetes had had an eye examination within the last year, and just over one-in-ten had sight problems [46].

According to the 2008 NIEHS, blindness was six times more common for Indigenous adults than for total population adults [46]. The main causes of blindness for Indigenous adults were:

- cataracts

- optic atrophy (damage to the eye’s nerves)

- refractive error

- diabetic eye disease

- trachoma.

For Indigenous children, the 2008 NIEHS found they had better vision than other children in Australia, especially in remote areas [46]. There were similar findings in the WAACHS [47]. The 2008 NATSISS found that almost one-in-ten Indigenous children had an eye or sight problem [48].

What is known about ear health in the Indigenous population?

Ear health is very important for hearing, learning and balance [49]. If ears get damaged, people might:

- not be able to hear properly, either for a short time, a long time, or for the rest of their lives

- have problems learning (because they cannot hear)

- have problems learning to speak properly.

There are a number of ear diseases, but the most common is called otitis media (OM) [49]. OM is an ear disease where the middle ear is affected by infection from bacteria or viruses. OM can be very painful and sometimes damages the ear drum and fluid can leak from the ear (known as ‘runny ear’). In another type of OM, fluid builds up in the middle ear without damaging the ear drum (‘glue ear’). Both types of OM can cause hearing loss. Ear disease is associated with people living in crowded homes (particularly with people who smoke), living in poor conditions, or having poor hygiene. Children who go to day-care centres are often more likely than others to get ear infections.

The 2008 NATSISS found that one-in-ten Indigenous children had ear or hearing problems [48]. In the 2004-2005 NATSIHS, ear/hearing problems were reported by one-in-eight Indigenous people (which was the same as for non-Indigenous people) [15].

Indigenous people, especially children and young adults, have more ear disease and hearing loss than do other Australians [49][50].

The 2004-2005 NATSIHS reported that OM was much more common for children than adults, and it was more common for Indigenous children than for non-Indigenous children [15]. OM was more common for Indigenous people living in remote areas (4%) than for those living in non-remote areas (2%). Indigenous people were three times more likely than non-Indigenous people to have had OM as a long-term health condition.

The 2004-2005 NATSIHS found that almost one-in-ten Indigenous people were partially or completely deaf [15]. Partial or complete deafness was more likely to affect Indigenous people than non-Indigenous people aged less than 55 years, but the rates were similar for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people aged 55 years and older.

The WAACHS found that almost one-in-five Indigenous children had recurring ear infections (ear infections that keep coming back) [47]. Young children (0-11 years) were more likely to have recurring ear infections than were older children (12-17 years). Hearing that wasn’t normal was reported by their carers for 7% of Indigenous children. There is a strong link between recurring ear infections and abnormal hearing: 28% of children who had recurring ear infections with discharge (runny ears) also had abnormal hearing, compared with 1% of those without ear infections.

In the NT in 2007-2012, two-out-of-three Indigenous children who had child health checks with an ear, nose and throat examination had at least one middle ear condition [51]. For Indigenous children who had a follow-up hearing test, more than one-half had hearing loss in at least one ear.

What is known about oral health in the Indigenous population?

Oral health is a term used to talk about the health of a person's teeth and gums [52]. If people have unhealthy teeth and gums they will probably have some pain; they may not be able to eat a variety of healthy foods or talk to other people comfortably. Two common oral health problems are caries and gum diseases. Caries is caused by bacteria that decay (break down) the enamel (hard outer part of the tooth); if caries is not treated the tooth will continue to decay and will eventually have to be removed. Caries is caused by eating a lot of sticky and sweet foods that let bacteria to grow and multiply. Gum disease (also known as periodontal disease) is caused by bacteria that attack the gums causing them to swell and bleed. If gum disease is not treated, the gums start to break down and the teeth will become loose because the gums won’t be strong enough to hold them in place. Gum disease is caused by poor oral hygiene (poor care of the teeth and gums).

The oral health of Indigenous people is not as good as that of other Australians. The oral health of young non-Indigenous children has improved in recent years, but the oral health of young Indigenous children has generally worsened [53]. Indigenous children have more caries in their deciduous (baby) and permanent (adult) teeth than do non-Indigenous children, and their caries are often more severe. Indigenous children have more decayed, missing and filled teeth than do non-Indigenous children. In 2000-2003, Indigenous children also had more gingivitis (a mild form of periodontal disease) than did non-Indigenous children.

Indigenous adults had more than twice as much caries as non-Indigenous adults, and had three times the number of decayed surfaces, which often suggests poor access to timely dental care [54]. Indigenous adults also suffered from more periodontal disease than did non-Indigenous adults. More Indigenous adults than non-Indigenous adults suffered from edentulism (losing all of their teeth), especially at younger ages.

What is known about disability in the Indigenous population?

Disability may affect how a person moves around and looks after themselves, how they learn, or how they communicate[55][56]. There are a lot of different kinds of disability:

- some affect the body, others affect how the brain works

- some are temporary, others last for a person’s whole life

- some people are born with a disability, some people become disabled as the result of an event (such as a car crash).

A disability that is severe and affects how a person is able to live their life is classified as a 'profound/severe core activity restriction' [57].

In 2008, one-half of Indigenous adults had some form of disability [57]. Around one-in-twelve Indigenous adults had a profound/severe core activity restriction.

Disability becomes more common as people get older [25]. In 2008, disability, including profound/severe core restrictions, were more common for Indigenous adults than non-Indigenous adults in every age-group (Figure 6), and a higher proportion of Indigenous adults required assistance with a core activity from a younger age. Overall, Indigenous adults were more than twice as likely as non-Indigenous adults to have a profound/severe core restriction [57].

Figure 6. Proportions (%) of Indigenous and non-Indigenous adults with a profound/severe core restriction, by age-group (years), Australia (non-remote areas), 2008

What is known about communicable diseases in the Indigenous population?

Communicable diseases are diseases that are passed from person to person either by direct contact with an infected person or indirectly, such as through contaminated (dirty/unclean) food or water. Another example of indirect transmission is when the disease is spread through the air, such as when an infected person coughs or sneezes and another person breathes in the air that contains the germ. Communicable diseases can be caused by:

- bacteria (e.g. tuberculosis)

- viruses (e.g. HIV)

- fungi (e.g. tinea)

- parasites (e.g. malaria) [58].

Improvements to personal and environmental cleanliness, and the introduction of new immunisations (vaccines), have greatly reduced the number of people who catch some communicable diseases [59].

If a person contracts (catches/develops) certain communicable diseases (like tuberculosis), the disease must be ‘notified’; this means that the information is collected by health authorities. Unfortunately, Indigenous status is often not reported in notifications. Only WA, SA, and the NT reliably identify Indigenous status in the notification of communicable diseases [60].

Recent information about communicable diseases include:

Tuberculosis: a lung infection caused by a bacterium that can trigger a range of symptoms, such as coughing, weight loss, and fever [61].

- Tuberculosis notifications were 11 times higher for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people in 2005-2009 (Derived from [34][62][63][64][65][66]).

Hepatitis: an inflammation of the liver caused by viral infections, alcohol or other drugs, toxins, or an attack by the body’s immune system on itself [67]).

- In 2009-2011, notification rates for hepatitis C were almost four times higher for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people.

- In 2009-2011, hepatitis B notification rates were similar for both populations.

- In 2009-2011, notification rates for hepatitis A were much lower for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people (Derived from [34][68][69][70][71]).

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib): a bacterium that can cause a range of illnesses, such as meningitis, septicaemia, and pneumonia [72]).

- Notification rates for Hib were 20 times higher for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people in 2010 [73].

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD): caused by a bacterium and can lead to several major health conditions, such as pneumonia and meningitis [74]).

- Notification rates for IPD were more than seven times higher for Indigenous people than for other Australians in 2006-2008 [16][75][76].

Meningococcal disease: caused by a bacterium and can lead to meningitis, meningococcaemia without meningitis, and septic arthritis [74][77]) .

- Notification rates for Indigenous children aged 0-4 years were nearly five times higher than those for non-Indigenous children in 2003-2006 [77].

Sexually transmissible infections: caused by bacteria and viruses and can lead, if left untreated, to a range of health conditions, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (blocked tubes) in women [78][79]).

- Notification rates for gonorrhoea, syphilis, and chlamydia were 5.5 to 64 times higher for Indigenous people than for non-Indigenous people in 2009-2011 (Derived from [34][68][69][70][71]).

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus): an infection that destroys cells in the body’s immune system [80]).

- In 2011, the rate of HIV diagnosis was similar for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people [81].

What is known about factors contributing to ill-health in the Indigenous population?

Nutrition

If a person eats healthy food they are more likely to be healthy [82]. A healthy diet includes:

- fresh vegetables and fruits

- whole grains

- low-fat dairy products

- lean meats

- foods low in fat and salt.

Having access to healthy foods can be a challenge for some Indigenous people who live in remote locations because food that has to be shipped over long distances is not always available, or because fresh foods may be expensive [82].

The 2004-2005 NATSIHS found that most Indigenous people ate fruit (86%) and vegetables (95%) every day [15]. Around one-in-eight Indigenous people did not eat fruit everyday (compared to one-in-14 for non-Indigenous people) and around one-in-20 did not eat vegetables every day (compared with one-in-100 for non-Indigenous people). More Indigenous people living in non-remote areas ate fruits and vegetables daily than did those living in remote areas. This may be because fruit and vegetables are more available and less expensive in non-remote areas than in remote areas.

The 2004-2005 NATSIHS found that most Indigenous people drank whole milk, and only around one-in-six Indigenous people drank reduced fat or skim milk [15]. About one-half of Indigenous people usually added salt to their food after it was cooked.

Physical activity

Keeping physically active is important for staying healthy. Physical exercise is good for a person’s social and emotional wellbeing and reduces the risks of heart problems, diabetes, and some cancers [83].

The 2008 NATSISS found that three-quarters of Indigenous children had been active for at least one hour on every day in the week before the survey [48]. Very few children (3%) did no physical activity the week before the survey.

For Indigenous adults, the 2008 NATSISS found that around one-third had taken part in physical activity or sport in the 12 months before the survey (Derived from [84]).

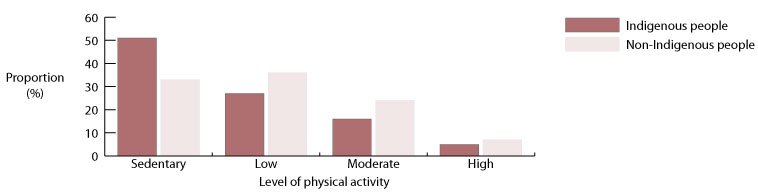

The most recent data that can compare the physical activity of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people is from the 2004-2005 NATSIHS. This survey found that more Indigenous people than non-Indigenous people were sedentary (had very little or no exercise) [16]. One-half of the Indigenous people in the survey reported that they were sedentary compared with one-third of non-Indigenous people (Figure 7). Around one-fifth of Indigenous people and one-third of non-Indigenous people had moderate or high levels of physical activity.

Figure 7. Proportions (%) of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people by levels of physical activity, Australia, 2004-2005

Tobacco use

Smoking tobacco is a major cause of:

- heart disease

- stroke

- some cancers

- lung disease

- a variety of other health conditions [85].

Passive smoking (breathing in another person's tobacco smoke) also contributes to poor health, particularly for children[85].

The proportion of Indigenous adults who smoke declined slightly between 1994 and 2008 (from 51% to 47%), but smoking was still more than twice as common among Indigenous adults than among non-Indigenous adults in 2008 [48]. There has been a reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked daily by Indigenous people between 1994 and 2008 [86]. According to the 2008 survey, two-out-of-three Indigenous current daily smokers had tried to quit in the previous year [57].

In 2008, around one-in-six Indigenous children 0-3 years and one-quarter of Indigenous children 4-14 years lived with someone who usually smoked inside the house [87][88]. Around one-quarter of Indigenous adults were living with someone who usually smoked inside the house [57].

Tobacco use was responsible for one-in-five deaths among Indigenous people in 2003 [89].

Alcohol use

Drinking too much alcohol is associated with:

- health conditions like liver disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers

- brain damage

- injury and violence

- self-harm [90].

If a woman drinks alcohol when she is pregnant, the unborn child may be affected by foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), the term used to describe the physical, behavioural, and learning problems caused by alcohol damage to the brain and other parts of the body of the unborn baby [91]. The 2008 NATSISS found that 80% of mothers of Indigenous children 0-3 years did not drink during pregnancy, and 16% drank less alcohol [16]. Only 3.3% drank the same amount or more alcohol during pregnancy.

Indigenous people are much more likely to not drink alcohol (abstain) than non-Indigenous people. The 2008 NATSISS found that more than one-third of Indigenous adults did not drink alcohol (compared with around one-in-eight of non-Indigenous adults) [92][93]. However, Indigenous people who drink alcohol are more likely to drink it at high-risk levels than non-Indigenous people. The 2008 NATSISS found that one-in-six Indigenous adults were drinking at high-risk levels for a long time (‘chronic’ risky/high-risk drinking), and one-third of Indigenous adults had reported drinking at high-risk levels over a short time (binge drinking) in the two weeks before they were interviewed [57].

In 2006-2010, alcohol was responsible for almost 400 deaths of Indigenous people [13]. Most of these deaths were from alcoholic liver disease.

Concluding comments

Indigenous people in Australia are not as healthy as non-Indigenous people but there have been a number of improvements, including:

- reductions in death rates [13]

- a decrease in infant mortality rates [13]

- a decrease in deaths from some diseases, like respiratory conditions, stroke and kidney problems [94]

- a decrease in some diseases, like trachoma [46] and tuberculosis [64]

- reductions in some communicable diseases (largely because more Indigenous people are getting vaccinated) [77][95]

- a decrease in smoking [48], and a decrease the number of cigarettes smoked per day by Indigenous people [86].

The reasons why the health of Indigenous people is worse than that of non-Indigenous people are complex, but represent a combination of general factors (like education, employment, income, and socioeconomic status) and factors having to do with the health sector (like not having access to culturally appropriate services or support).

Within the health sector, there is a need for:

- more health advancement programs

- better identification of health conditions before they become serious

- more primary health care services that are accessible to Indigenous people

- greater cultural competence of service providers.

The achievement of substantial health improvements for the Indigenous population will require the ongoing commitment by all Australian governments through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) to ‘closing the gap’ in health and other disadvantages between Indigenous and other Australians.

In addressing the COAG ‘closing the gap’ commitments, the Australian and state and territory governments allocated $4.6 billion over four years to address early childhood development, health, housing, economic participation, and remote service delivery. COAG also achieved a number of supportive commitments by the corporate and community sectors.

The COAG commitments to date are encouraging, but ‘closing the gaps’ in health and other disadvantages will not be achieved in the short to medium-term. Achievement of the necessary improvements in the health and wellbeing of Indigenous people will depend largely on a long-term commitment by all Australian governments. This commitment will need to include strategies that fully address health services and the social and other factors that affect the health disadvantages faced by Indigenous people.

References

- Carson B, Dunbar T, Chenhall RD, Bailie R, eds. (2007) Social determinants of Indigenous health. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin

- Wilkinson R, Marmot M (2003) Social determinants of health: the solid facts. Denmark: World Health Organization

- Marmot M (2004) The status syndrome: how social standing affects our health and longevity. New York: Holt Paperbacks

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012) Australian demographic statistics, March quarter 2012. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Yap M, Biddle N (2012) Indigenous fertility and family formation: CAEPR Indigenous population project: 2011 census papers. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012) Census of population and housing - counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2011. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2010) Population characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006 (reissue). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009) Experimental estimates and projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians 1991 to 2021. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012) Births, Australia, 2011. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Li Z, Zeki R, Hilder L, Sullivan EA (2012) Australia's mothers and babies 2010. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare